Stepping off the plane in Vienna (for the first time), one cannot help but marvel at the anachronistic decor and positively provincial scale of this major city's international airport. The absence of customs clearance gives one a false sense of security, as if the policy of neutrality, adopted by Austria in 1955, is a comfortable womb that warmly ensconces all inhabitants of the city -temporary or otherwise. Precisely this instability leads the skeptical visitor to question the motives of this city in continuing to define itself as the epitome of European gentility while remaining conspicuously absent from all international accounts of politics and culture. Ever since the recuperation of an Austrian national identity after the German Anschluss, which effectively subsumed the eminence of fin-de-siecle Vienna under the dogma of National Socialism, a crisis situation has prevailed in which the producers of Austrian culture have focused their energies on the piecing together of their shattered past, while at the same time continually defending themselves against charges of obsolescence from the rest of Europe and beyond. It has been suggested that the period of German occupation erased any notion of an Austrian identity, and that at the close of this century, the country is only beginning to recover any sort of indigenous presence.

The capital city of Vienna, while retaining its architectural glory and its revered classical music productions, has entered a prolonged period of cultural stagnation. Threatening to collapse into full-fledged auto-critique, without the presence of any comfortable distance or self-assurance, the past twenty or thirty years of Austrian art, architecture, music, and literature clearly exhibit a shared thread of pessimism and self-doubt. As is often the case, powerful and probing work is often born of adversity, if not of sheer stagnancy, and contemporary Austria is no exception. Painting, literature, and music can always thrive in such an environment, but the threat to architecture, to the very core of urban existence, transcends private boundaries into the public realm. But the questions remain: How can the classical economy of forms be supported within an urban environment that no longer believes in its capacity to sustain the myth of its own validity? And what shape shall be given to these "anti-forms," born of the effort of trying to recall a long-lost grandeur that had missed the opportunity to evolve with impunity over the past fifty years of its own existence? Can an aesthetic be created out of the style of "becoming," of the not-yet-formed? Or, instead of incipience, perhaps these are forms that constantly are at battle with themselves, fighting from the inside out? And at what stage will this new aesthetic be momentarily arrested so as to make itself available to its critics?

Two separate answers to that question have been posited by two architectural concerns, Hans Hollein, and Coop Himmelblau (Wolf Prix and Helmut Swiczinsky). Both these firms came to maturity in the late 1960's during the initial crisis of self-doubt where architecture was literally dismantled and started afresh as a means of erasing historicism Ñboth Austrian and German. Rather than striving towards any sort of utopian impulses as a curative for the dissolution of Austrian nationalism, the works of Coop Himmelblau and Hollein remain almost painfully aware of their dichotomous role as public displays of private sentiments, invoking the dissolution of the past along with visions of reconstruction.

The use of architecture as a social mobilizer is hardly a new concept, nor is the infusion of buildings with a social agenda; Coop Himmelblau and Hollein, however, approach their solutions to the same problems from opposite ends of the spectrum of skepticism. Plumbing the poles of, on the one hand, self-pity, and on the other, stubborn pride in the face of adversity, these two architectural firms embody a sophisticated model of Austria's postwar consciousness that seeks to dismantle the ornamental facade of historicism by looking critically at the ways in which the history of a particular medium is addressed by later practitioners.

Hollein's work seems to issue from a spirit of redemption, rising from the ashes in a decidedly optimistic vision of the power of built forms to convey a sense of pregnant hope. Coop Himmelblau offers an architecture of apology, as if the rendering of the materials- offered as humble apologies to the memory of lost greatness- is cognizant of its own inadequacies. Dispensing with historicity and materialism as recognizable cultural artifacts, especially in the vulgarized form that renders most postmodern architectural production a merely superficial index of commodity culture, the architectural projects of Hollein and Coop Himmelblau enact a variant of Frampton's ``critical regionalism,'' which calls for a response to intrinsic local traditions and values- both physical and supraphysical- dialectically conceived in relation with the incursion of outside (read: alien) influences 2. Rather than invoking vernacular materials and building methods, these architects cull their imagery and value systems from the local psychological landscape, presenting a rhetorical strategy that locates both the native and the alien within the same forms. Insofar as any sort of shared consciousness can be said to exist in contemporary Austria as regards the downsizing of its international stature, both Coop Himmelblau and Hans Hollein trade upon this insecurity as a means towards understanding how the situation may have come about, how it is in the process of repairing itself (if at all), as well as the emotional component that might dictate the prognosis for a national rehabilitation.

The resulting forms do not so much participate in a trajectory of Viennese architecture, but rather in a type of automatism that probes the presumed collective psyche of the Viennese populace. Wolf Prix, one of the Coop Himmelblau's principals, has spoken of the removal of "circumstantial pressure and complexity" through a deliberate obliviousness to architectural historical laws, to the need for clients, and to money as a motivating factor in design.3 By removing these materialist obstacles, Prix and Swiczinsky are able to operate on the level of pure form.

Coop Himmelblau brilliantly uses the language of deconstruction and postmodernist architecture to comment on these manifestations of the architectural neo-avant-garde, vilifying the presumed aestheticization of the style and parodying its false motives. The work of Peter Eisenman and Bernard Tschumi, for example, strives towards a willful and theoretical deformation, conjuring up impossibly problematized architectural forms as a means of confusing traditional narratives of space as they bear upon aspects of the external and internal promenades architecturales. Architect/theorists such as Eisenman and Tschumi use their own writings to legitimize their architectural projects- a self-reflexivity that isn't without merit, at least as a jumping-off point for radicalizing the trajectory of built forms 4. Coop Himmelblau upsets the elitist nature of these projects with a deliberately apologetic program, using the innately tenuous aspects of architecture -- such as tension, counterbalance, transparency -- to destabilize their works, allowing the sheer force of building materials to impact upon their structural selves and inducing a struggle from within the actual materials.

The "tenuous aspects of architecture" mentioned above are described as such for the implicit dialectic that governs their function, each element resting (albeit fitfully) in an interstitial state of flux, consistently denying resolution as a prerequisite for use. But the counterweight that guarantees the efficacy of a cantilever is the mere dialectical partner of the cantilever itself. Coop Himmelblau transgress the meaning of the cantilever and the counterweight in search of something beyond mere physics, something capable of destroying in order to recover -- as in Georges Bataille's conception of the informe5 -- an eruption from within that nevertheless proceeds from a strict adherence to structural rules: the very nature of the building's undoing is its willful neglect of that which is required to hold it erect.

In his introduction to the catalogue of the Deconstructivist Architecture show- co-curated with Philip Johnson in 1988 for the Museum of Modern Art- Mark Wigley hints at the processes behind deconstruction, suggesting that the new architecture is no longer "the conflict between pure forms," but that "(the) forms themselves are infiltrated with the characteristic skewed geometry, and distorted."6 Wigley continues to describe Coop Himmelblau's law office reconstruction (Vienna, 1989) as taking shape via "the alien emerging out of the stairs, the walls....,"without fully recognizing the implications of self-reflexivity he attributes to these disintegrating forms. The agenda of Coop Himmelblau requires this putrefaction, and the city clamors for the "alien" forces, the uncertainty of instability, anything to upset the stagnant air of history. Admitting that this antipathetic impetus must come from within the form that it seeks to disrupt is to adduce that an unnatural reliance on the past can only be undone through a painful reversal of the very forms that restrain.

The strategies against architecture7 have been present from their earliest

performances and projects, and came to fruition in their works of the late

1970s and early 1980s. Their Roter Engel Bar (Vienna, 1980Ð81)

continues the practice of exploring unorthodox relationships between interior

and exterior by incorporating a vaguely ovoid shape of stainless steel

(the angel's `wing') that weaves in and out of the

small ground floor space, at one point veering out six feet from the exterior

wall, reentering the building through a minute hole in the masonry only

to terminate in two jutting points over the door to the interior courtyard

in a manner similar to the Secession building project (discussed below).

Essentially an interior design, Coop Himmelblau's `angel' enlarges its protectorate by extending onto the street, at the same time

circumscribing an imaginary space only vaguely related to the interior

of the bar. Like Eisenman's cubic displacements, the Roter Engel

is a transformation of a core space, but instead of merely pivoting on

a central axis, it literally makes a break for the outside, the scored

masonry of the older building unable to keep it at bay. The angel's

renegade nature presents a challenge as much to the composure of historical

forms as to the contemporary viewer who is forced to cope with its restlessness.

interior of the Rote Engel Bar

Aestheticism has often been a means for architects to confuse, or even to veil, the ideological component of their work, a practice that tends to dismiss what has proven to be an effective argument for the concept of a coding of space that is politically, sociologically, and/or culturally oriented. In the latter formulation, we allow space to inhabit a dynamic role, to claim agency as a discrete and organic entity rather than as a repository for attributes resulting from its various usages. By seeking to annihilate any traditional expectations of beauty in a given building, the architect is forcing the visitor/viewer to acknowledge the envelope or enclosure as a cordoning off of a particular segment of the world, in order to be impregnated with specific physical and emotional attributes and functions. When an architecture renounces its materiality, or at least calls it into question, it stands at odds with the predominant trait of the medium, namely its functionality. Architectural practice that intentionally problematizes and/or dismantles its functionalism relies on the material itself, rather than the design, as a means of support, transferring agency from the architect to the built form. The architecture considered in the present study, however, problematizes the very nature of the materials used, as they are deployed without complete confidence in their structural efficiency. A means of symbolically challenging the historically secure wall or ceiling plane, Hollein and Coop Himmelblau play often with the trope of the fissure, often literally a crack in the interior or exterior wall, serving not as a spatial divider but as an aestheticized flaw integrated into the building's design.

The fissure is engaged, perhaps, as a critique of the ephemerality of

the International Style, wherein the tectonic thrust was directed more

towards maintaining the illusion of the building's weightlessness

than in reference to the actual means of support. But as is evident from

a comparison between the way that the fissure is used in two works, Coop

Himmelblau's Reiss Bar in Vienna (1977) and Hollein's Rauchstrasse

Haus 8 in Berlin (1983-5), the space of divergence as it appears on/in

the surface serves two different purposes, in each case underscoring the

leitmotif of the respective architectural practice. The exterior of Hollein's

apartments, constructed as part of the I.B.A. project in Berlin, features

a pink center section scored into odd, asymmetrical patterns, the resulting

`cracks'; thus refusing any orthogonal ordering while remaining

superficial so as to retain the unity of the supporting wall. Although

appearing to have been pieced together after having been destroyed, the

wall coheres in a way so as to play with the notion of dismantling, to

affirm that the fracturing of the assembled blocks is mere illusion, not

reality. By ultimately retaining the stability of the wall, Hollein's

building attaches to an inner logic that maintains the structural integrity

of the facade while giving the sense that the building has been halted

for evaluation at a precise yet incomplete moment of its reconstruction.

By refusing to finish the wall in a traditionally prescribed fashion, Hollein

hints at the additional steps necessary for a full recuperation of a united

Berlin, the project having been completed while the infamous wall was still

standing.

plan of Rote Engel Bar

plan of Rote Engel Bar

The name of Coop Himmelblau's Reiss Bar plays on the German verb meaning to tear or split8, taking as its foundational principle a quote from National Geographic Magazine that refers literally to California, and metaphorically to Vienna: "The most fascinating thing about San Francisco is being in a city that is built on a crack in the earth's crust and never having that feeling."9 The ancient ties between literature and architecture are used not as a source of strength or beauty (as in the qualities of an orator's skill being compared to a building's formal harmony) but of weakness, by literally engaging a crack into the infrastructure of this small champagne bar in Vienna's first district as a challenge to the purity of the internal wall. Less an overt commentary than a decorative motif, the wall riven into two sections seems captured in the moment of moving apart, rather than in the process of joining. The preparatory sketch for the bar shows the motif as a vibrating, painful rift threatening to engulf the solid space of the bar; shapeless and divisive in the sketch, the stylized look of the final version avoids any unsettling sense of displacement, while affirming the projects intent in overturning any normative sense of complacency. The bar's interior is thus subtly transformed into a non-threatening arena for the discussion of transition, decay, and reformation. But whereas Hollein presents rupture at a state of reparation, Coop Himmelblau arrests the process of unification at a point midway between completion and collapse; sheer tectonic force has triumphed over the humble will of the architects, as if to admit that the chance for failure is equal to, if not greater than, that for success.

Earlier the word rehabilitation was used deliberately in order to invoke the therapeutic nature of these architectural practices. Both architectural firms adopt the stance of the physician, which may be the most appropriate metaphor for their chosen roles, the difference lying in the separate practices that each accepts. Coop Himmelblau might be likened to an army field doctor, patching together wounded soldiers with perfunctory and temporary solutions. Hollein would be the urbane plastic surgeon, recasting the whole of a damaged site into a new and synthetically improved state. In this case, Hollein must grapple with the inherent inadequacies of going against the natural order of things, offering solutions for the reconfiguration of sites and buildings that are ill-conceived, or that have grown old.

To the extent that Coop Himmelblau attempts to create an architecture of decay, Hollein may be said to explore the process of rebirth. His major works are buildings and projects that seem caught in a process of becoming -- only partially formed but redolent with the suspicion that completion is imminent. Hans Hollein's New Haas Haus builds upon the site of two previous incarnations of the Haas Haus, and reconfigures the idea of the public building into a pastiche of hopeful symbolism. Hollein, unlike Prix and Swiczinsky, reserves his ties to the past for guidance and strength, understanding the recuperation of glory to be intrinsically tied to transformation of the past. Hollein's first retrospective, held at the Pompidou Center in 1987 was called Métaphores et Métamorphoses. The title is significant in pointing to the architect's reliance on the past, specifically in the sense that both metaphors and metamorphoses require an antecedent around which the particular action or allusion is to occur. In an interview appearing in the catalogue, Hollein states: "Life without history would be unthinkable and, for me, architecture without history would be no less unthinkable."10Hollein completely rethinks the site of the Haas Haus, which lies at the most crucial and public intersection of Vienna's pedestrian zone, diagonally across from the Cathedral of St. Stephan. Hollein allows the monumentality of the site to accept the lion's share of attention, and the actual structure of the Haas Haus is quite modest in size. Its success is based on the southwestern facade that faces away from the cathedral; here Hollein captures the spirit of redemption in a massive, sheer wall of glass and steel that gradually emerges from within a scored metal shell. Peter Eisenman writes in praise of the building:

"[The Haas Haus] become[s] a figural building in itself, both in its form and its material content. Second, the new Haas house represents another kind of contextualism in a true postmodern sense. Because it works two themes simultaneously; it creates a `tabula rasa' by removing the existing building. This in itself is an extraordinary political gesture, but then it rebuilds the context in a rather non-contextual manner. It creates a deeply eroded and fractured building, which in its metal and glass exterior foreshadows the complex unfolding of its interior contents."11

Hollein's project is not so much an erasure of the former building, but a recuperation of its function as multi-use public space addressed through a more contemporary stylization. The facade mentioned above, as well as in Eisenman's statement, alludes to the way in which the new building can be seen to emerge from the ashes of the old, still within sight of salvation.

No longer are the site and its intended building meant as a tabula rasa

for the present or future generation, nor do they stand as a heroic triumph

over past woes; even the most public building built by either of these

architects, Hollein's New Haas Haus (Vienna, 1992), resolutely avoids

any sense of monumentality in favor of a relatively tentative step in the

process of recovery. It might be easier to understand these projects as

anthropomorphized to the point of physical vulnerability (a trait normally

antithetical to architecture; hence, deeply ironic), fundamentally rejecting

any and all of the monolithic and totalizing modernist myths, concentrating

instead on the particular rather than the general, finding solutions (or

propositions thereof) in the cracks and interstices of contemporary Viennese

consciousness. The aesthetic impulse thus plays a supporting role to the

functional role of the building; however, functional, in this case, means

something different than the early twentieth-century definition of the

term. Now, at the close of the millennium, functionalism has moved beyond

its ties to the machine to incorporate the mobilizations of any generative

impulse, including the cultural. 12

Coop Himmelblau proposes a type of anthropomorphism

predicated on lack rather than substance. Whereas the tradition of architecture

from the Greeks onwards can be said to have based systems of measurement

on the scale of human proportions, Coop Himmelblau uses a radically divergent

measure of man: that of his deficiencies. Because the range of human faults

is far greater even than the scope of differing physiques, Coop Himmelblau's

architecture must resist any codified or normative style, attempting, instead,

to allow the idiosyncrasies of each potential inhabitant to recover themselves

in relation to the experience of the building. Perhaps the best example

is the Open House of 1983. The initial sketch for this work, conceived

through a long period of contemplation on the concept, followed by several

seconds of frenzied activity with pencil and paper, appears as the work

of an invalid or a schizophrenic: orthogonals refuse to meet one another,

spidery tendrils creep off to the side without purpose, the whole work

situated in an impossible space, stabilized only by the hesitant inclusion

of a ground line. Coop Himmelblau writes: "The distribution of the

100 m2 area is not predefined. It may be determined after the building

is completed or not at all."13 Radically different from the Corbusier's

plan libre, which frees the interior space but subjects it to a stifling

predisposition towards orthogonal configuration, the Open House is exactly

neutral in its projections of the deployment of spatial configurations,

allowing for the space to conform itself, once again in a self-reflexive

mechanism that always harbors an equal chance of success or failure. Prix

confirms the instability of the house's psychic and physical identity,

at the same time reinforcing the architect's position as nurturer

of the terminally ill: "The house is very complicated and is therefore

like the disabled child which we love very much." 14

Coop Himmelblau's most celebrated work, completed in 1989, is previously mentioned rooftop law offices in Vienna. The structure, situated five minutes from both Wagner's Postsparkasse and Hollein's Haas Haus in the most architecturally fertile part of Vienna's first district, hangs precariously from its perch atop a nondescript nineteenth-century building like a bird caught in an electrical wire. A slightly more robust version of the Open House (discussed below), the law office, which was featured in the Deconstructivist Architecture show, resists any reading of itself as a pleasing entity, literally challenging the viewer to find enjoyment in its appearance. Making no effort to harmonize with the building on which it balances, the entire structure seems to sway with the breeze, threatening at any instant to topple onto the street below. The only safeguard against disaster appears to be a taut bow-shaped truss, groaning under the strain of its load, but fortunately buttressed from below by a secondary (and hidden) steel and concrete foundation that offsets the lateral load, thus relieving the weight on the non-load-bearing walls of the older structure.

Hollein and Coop Himmelblau's ties to the past are no more poignantly expressed than in two projects directly related to the historical eminence of Vienna. Although admittedly ten years apart, these projects highlight the specific differences between an aesthetic of redemption (Hollein) and of decay (Coop Himmelblau). Hollein's new facade for the Kuenstlerhaus Vienna (1989) -- created for the exhibition held in the same year entitled Traum und Wirklichkeit (Dream and Reality) -- adds to a group of similar transformations to which he has subjected the same building. He recasts the neoclassical facade in a postmodern pastiche of familiar expressionist symbols, using a female figure from a controversial Klimt mural set off against a segment from Karl Ehn's Karl-Marx Hof (Vienna, 1927) -- the two together embodying the antipodal realms of the exhibition's title. Hollein understands completely the ironic cultural shift that allows for these two works to be used as symbols of the city's glorious past, given that neither the Klimt nor the Ehn housing estate presumably reflects Austria's most cherished contributions to twentieth-century culture:15 the Klimt mural was, as was often the case, a scandal, while the Karl Marx Hof recalls an impoverished period in Vienna's recent history wherein subsidized housing appeared as a means of salvation. The Klimt figure reappears around the same time in the interior of the New Haas Haus, with arms raised in victory, hardly unaware of the candor with which she stands amid this new and controversial architectural form.

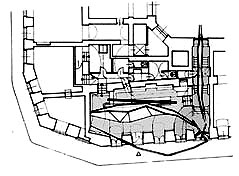

Coop Himmelblau forsakes such subtle irony for bluntness in their projected transformation of Olbrich's venerable Secession building for the 1979 Viennese Biennale. Neither exclusively an interior nor an exterior renovation, Coop Himmelblau's project, titled Vector, calls for a 54-meter long aluminum needle to enter the building from the rear and to emerge, point first, at the top of the main entrance, creating a macabre and foreboding canopy. Strangely, the project avoids any sentiments of violence by the grace and cleanliness with which the body of the extant structure is punctured as if by a surgical lance. The point clearly is to recontextualize the relationship of the interior to the exterior, by creating an extension that confuses the boundaries of the two in relation to this new formal element; as result, the viewer is destabilized in relation to the whole.

HERE

for more